The Fundamentals and Characteristics of VC Fund Distribution Process

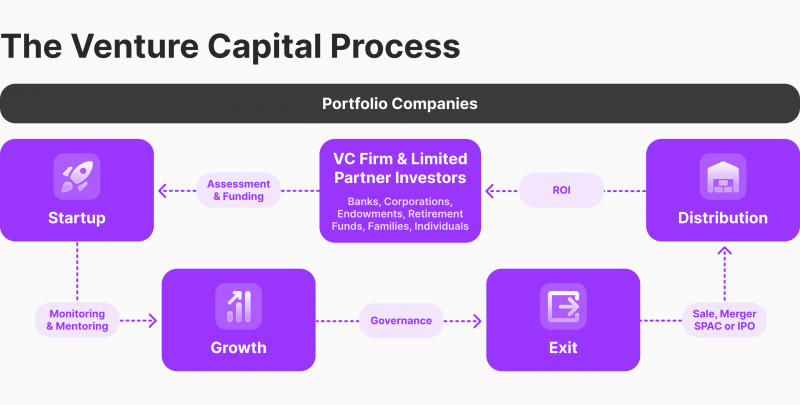

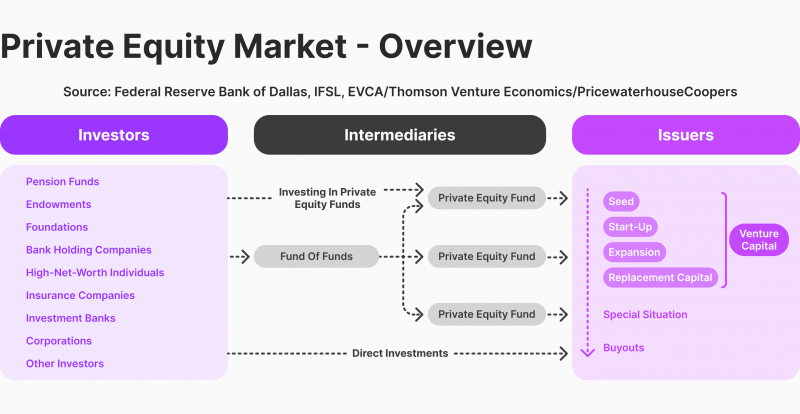

Today, a large share of the financial sector, in particular private equity organisations, are venture capital funds, which provide capital to start-ups in exchange for a share in the authorised capital.

As the most important source of financing for new companies, a venture capital fund is formed by an association of investors whose interest is the successful establishment of the invested business and the subsequent receipt of profit or capital, which the fund subsequently distributes to each of them in a certain proportion.

This article is intended to explain the concept of VC fund distribution and will tell you what a liquidity event is and what types there are. You will also learn what types of venture capital fund distributions are available and what mechanisms can be used when working with this financial product.

Key Takeaways

- VC fund distribution is the process of distributing capital from the fund to its investors in the form of a certain share of the profit generated by investing in a startup.

- The distribution of capital can be in the form of cash to all participants or in the form of securities.

- There are different types of allocations in terms of proportionality, including return on capital, catch up tranche, net asset value, slice and split models.

What is VC Fund Distribution?

Venture capital fund distributions refer to the disbursement of cash or securities from a VC fund to its investors. These distributions may take the form of a return of capital or a proportionate share of profits to which investors are entitled. The primary objective of the fund distribution process is to provide investors with a tangible benefit as a result of their investment in the fund.

Venture capital funds generally distribute funds to investors on a periodic basis, such as quarterly or annually. The capital distribution process is typically managed by the fund’s general partner, who is responsible for ensuring that the distribution of funds is fair and equitable to all investors.

For investors who have invested in a VC fund, their investment returns are realised in the form of distributions. These distributions are typically received through a check or wire transfer once the VC fund has exited its ownership position in one or more of the business entities in the fund’s portfolio, which can be regulated by the fund of funds venture capital firm.

This event is commonly referred to as a liquidity event, as it allows the fund to have sufficient capital on hand to distribute to the shareholders. Nonetheless, some funds may choose to wait until all positions have been closed before sending out the distributions to their investors.

A Fund-of-Fund company, which holds a portfolio of other investment funds, can be segmented by generalists, VC-specific, public, retail and VCs, considered the most prominent limited partners investing in VCs.

What Are the Types of Liquidity Events?

So, what is a liquidity event? The answer is pretty simple. All venture capital funds seek to ensure that the companies in their profile have experienced a liquidity event to realise a real return on their investment.

At the same time, there are several types of liquidity events depending on the conditions and peculiarities of the functioning of a venture distribution of capital funds. These include:

1. Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)

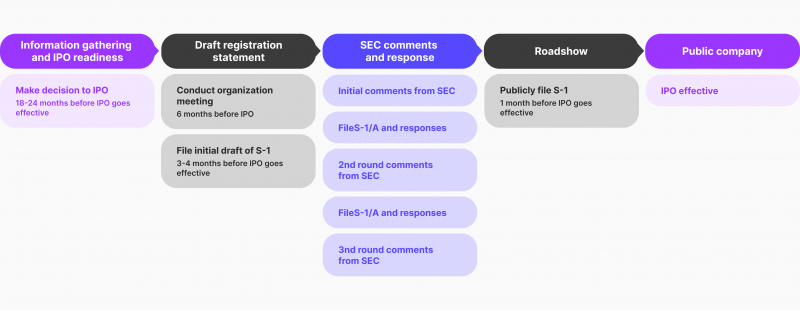

When a startup transitions to being publicly traded on a stock exchange like the NASDAQ or NYSE, it is commonly called “going public”. The most prevalent method for startups to achieve this is an IPO. Nevertheless, some companies, such as Roblox and Coinbase, have opted for a direct listing approach, where only existing shares are sold without the creation of new shares and without involving underwriters.

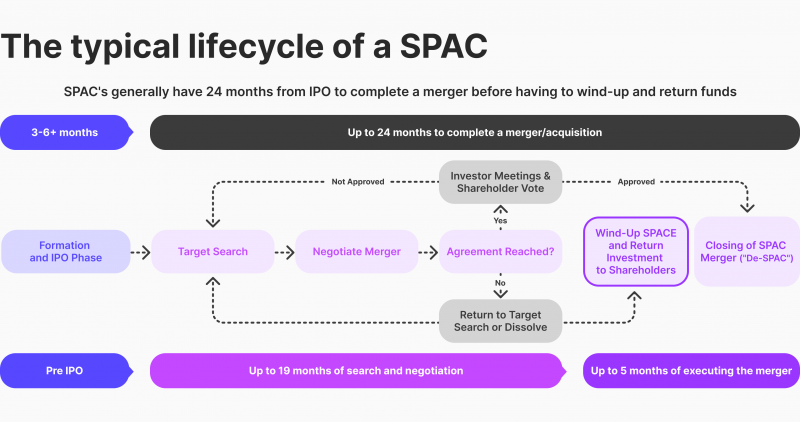

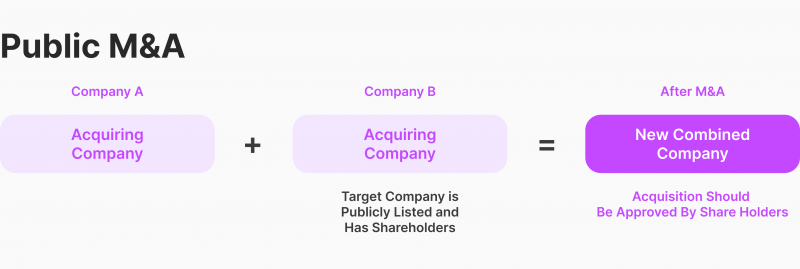

Another avenue for startups to become publicly traded is merging with a Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicle (SPAC) already listed on the stock exchange. Companies like SoFi, a fintech firm, have chosen this route to go public.

Following the public debut, current investors may face a lockup period, restricting them from selling their shares for a certain period, typically from 90 days to a year. This waiting period stabilises the market before existing investors can divest their stake in the company.

2. Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As)

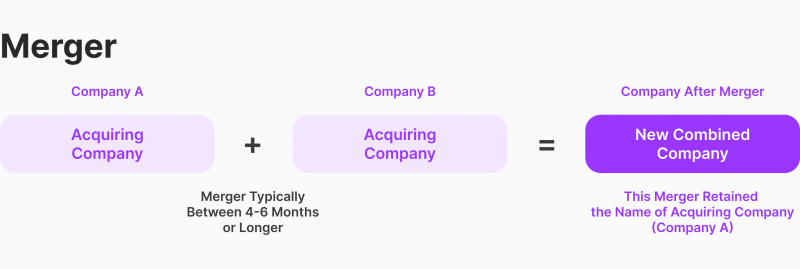

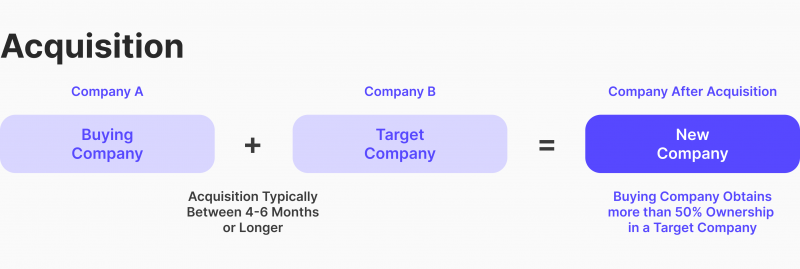

Within the realm of mergers and acquisitions (M&As), various terms may come across, such as buyouts, consolidations, acqui-hires, or restructurings. These terms all fall under the broader umbrella concept of M&A, encompassing various transaction types and strategies.

Acquisitions can be structured in two common ways. The first is a stock sale, where the target company’s stockholders sell their shares to the buyer. This results in the target company becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of the buyer.

In some cases, the buyer may absorb the target company, leading to the dissolution of the target as a separate entity. The second structure is an asset sale, where the target company sells most or all of its assets to the buyer. Following the sale, the target company basically dissolves and distributes the proceeds to its stockholders during the wind-down process.

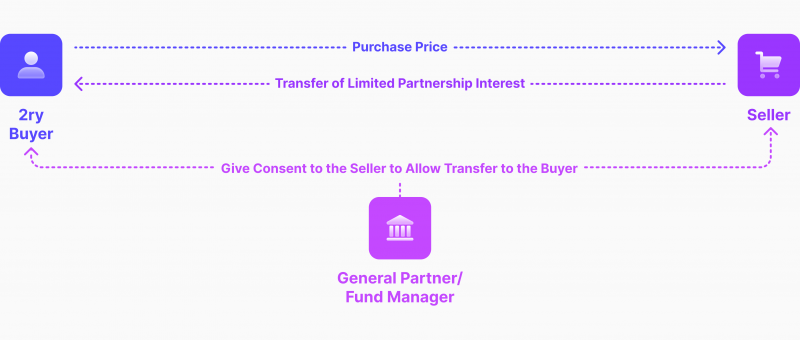

3. Secondary Transactions

A secondary market transaction occurs when investors purchase stock in a company from an existing shareholder rather than directly from the company in a primary stock sale. Common sellers in venture secondaries include venture capitalists, executives, and employees. This type of transaction allows investors to acquire shares from existing shareholders.

Venture secondary transactions are not limited to a specific timeframe but often occur within 90 days of a primary funding round. Companies typically cap the size of traditional venture rounds, making secondaries a chance for those who missed the initial investment opportunity to participate. It allows investors to join the company after the primary round has closed.

There are various forms of venture secondaries, with two main categories being structured liquidity programs and direct secondary sales. These transactions offer flexibility and options for investors looking to enter the market through existing shareholders.

Have a Question About Your Brokerage Setup?

Our team is here to guide you — whether you're starting out or expanding.

By participating in venture secondaries, investors can diversify their portfolios and potentially benefit from the growth of the company in which they are investing.

The Mechanisms of VC Fund Distributions

Despite the appealing returns investors find in these distributions, limited partners (LPs) may only sometimes be completely content upon receiving them. This is because the capital initially committed to the fund is typically in cash, but distributions to LPs can be made in cash or shares.

Cash distributions are normally executed when the startup issues dividends to venture capital funds, experiences a liquidity event through a merger or acquisition, sells its equity stake in the secondary market, or gets listed on a stock exchange, allowing VCs to sell their shares for cash distributions.

Dividend payments from a startup to its investors are rare. Still, when private equity funds are involved in the startup’s growth, they can employ recapitalisation (private equity distribution) and dividend payment strategies to mitigate investment risks and enhance returns.

Investors typically prefer the M&A route as an exit strategy. In this scenario, a strategic financial buyer acquires all the shares of the target company, requiring the majority of investors to approve the transaction.

Alternatively, early-stage investors who have already achieved substantial returns may participate in the secondary market, selling part or all of their stake to other investors with a different risk appetite and investment horizon, thereby securing their profits.

Cash Distributions

Typically, fund managers and limited partners prefer cash distributions as the primary mechanism for providing immediate liquidity to investors. Additionally, the valuation of the startup is defined, which streamlines the calculation of the financial profitability of the investment and the carry earned by the fund manager.

However, there are certain drawbacks associated with receiving cash-out distributions, including the possibility of lost earnings in the event of potential investment appreciation. Early exits in the investment cycle of the fund run the risk of rendering reinvestment of this capital impossible or, alternatively, reinvesting at a lower return.

Stock Distributions

An alternative method of distributing returns to investors in venture capital is through the distribution of shares. This distribution method usually occurs post-IPO, where venture capital funds distribute shares to their limited partners after the lock-up period.

Another common exit liquidity strategy is through Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs), which are publicly listed entities that acquire startups through a reverse merger.

This process allows the startup to be listed on the stock market, allowing investors to sell shares on the secondary market or hold onto them in anticipation of capital appreciation. In some cases, M&A transactions may involve the distribution of shares to limited partners instead of cash.

While distributing shares can offer potential capital appreciation and higher returns for LPs, it also comes with risks, such as the devaluation of the startup and potential share price depreciation. Additionally, calculating the carry for the general partner can be challenging, leading to implementing a 5 to 15-day moving average post-listing to mitigate stock price volatility in the initial trading days.

Fund managers must carefully consider the implications of different exit strategies to ensure the best outcomes for all parties involved in the investment partnership.

Major Kinds of VC Fund Distributions

When it comes to distributing capital investments between investors, it is customary to distinguish several fundamentally different schemes, each of which has its own characteristics and nuances of making a profit. Here are their varieties:

Deal-by-Deal Distribution Waterfall Model

Deal-by-deal waterfalls, a distribution VC model or arrangement where calculations are done separately for each investment, are often known as “US-style” waterfalls due to their prevalence among US-based managers. However, these types of waterfalls have become increasingly rare, even among US VC funds.

In recent years, deal-by-deal waterfalls have decreased in popularity, with many now incorporating a “whole fund” clawback provision. This means that sponsors must reimburse any excess carry if they still need to meet the preferred return on a whole-fund basis.

While some European VC firms still use deal-by-deal waterfalls, they typically follow a hybrid model that includes a “make whole” provision for losses, along with a “whole fund” clawback requirement.

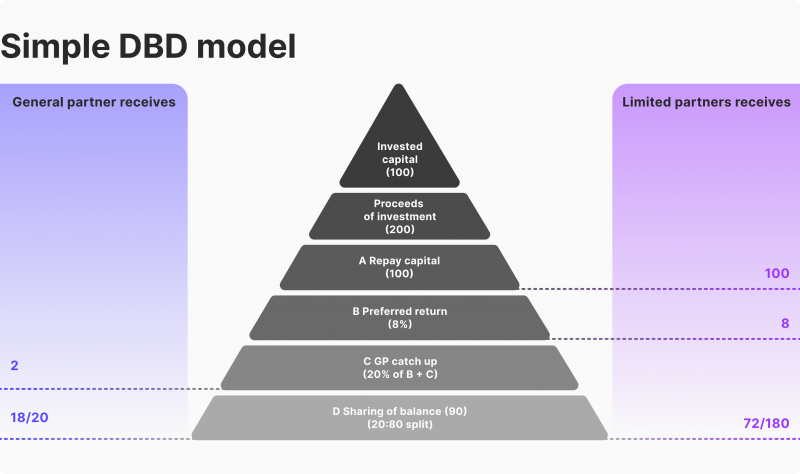

Though waterfall schedules may be customised, generally, the four tiers in a distribution waterfall are:

Return of Capital Contributions

In this mechanism, the general partner receives distributions once the limited partners have received distributions equal to the amount they have contributed. After that, 80% of the distributions go to the limited partners and 20% to the general partner.

This arrangement ensures that the limited partners receive the highest percentage of early distributions. This provides stability by eliminating clawback risk and any distributions made before all capital has been contributed. However, it also creates perverse incentives and timing disadvantages for the general partner.

Catch-Up Tranche

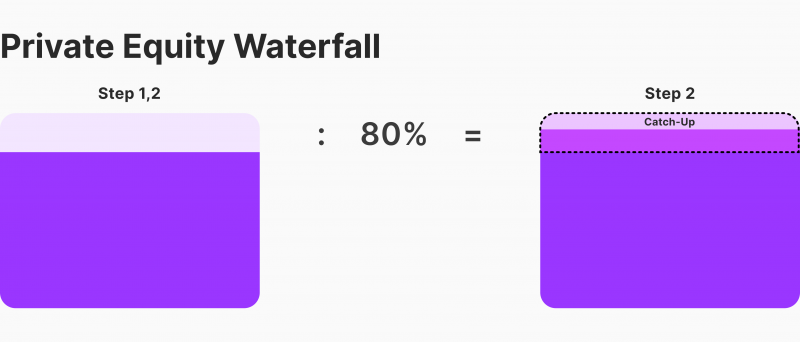

The mechanism resembles the previous method in prioritising the return of limited partner capital contributions before any distributions are given to the general partner.

However, once the LP’s capital contributions have been returned, the general partner receives 100 per cent (or 50 per cent in some cases) of subsequent distributions until it has received 20 per cent of all distributions made by the fund since its establishment.

After reaching this threshold, distributions are divided, with 80 per cent going to the limited partners and 20 per cent to the general partner.

While this arrangement does address the timing disadvantages faced by the general partner by allowing for a larger share of earlier distributions, it may inadvertently amplify perverse incentives and increase distributional gamesmanship due to the significant shifts in the general partner’s share of distributions at critical points. These shifts occur when the general partner’s share goes from zero to 100 (or 50) per cent and then decreases to 20 per cent.

Consequently, the general partner may be tempted to delay the distribution of particular securities in anticipation of an upcoming increase in their distribution share or expedite the distribution of such securities in anticipation of a forthcoming decrease.

Split Distributions

In this distribution arrangement, the available amount for distribution is divided into two distinct components: “return of capital” and “profit.” These components are associated with the cost basis and the distributed portfolio security appreciation.

In the case of a cash distribution, the portfolio security from which the cash was received by the fund is considered. The return of capital amounts is distributed solely to the limited partners. In contrast, the profit amounts are distributed with 80 per cent going to the limited partners and the remaining 20 per cent allocated to the general partner.

Net Asset Value

In this arrangement, the general partner is entitled to receive 20 per cent of each distribution, but only if the fund’s net asset value is equal to or greater than the total capital contributions made by the limited partners.

Another variation of this arrangement allows the general partner to receive 20 per cent of each distribution, but only if the fund’s net asset value exceeds the limited partners’ total capital contributions by a specified percentage (usually between 10 and 25 per cent).

Discover the Tools That Power 500+ Brokerages

Explore our complete ecosystem — from liquidity to CRM to trading infrastructure.

This additional cushion of assets minimises the risk of a clawback, as it increases the number of losses that would need to be incurred before the general partner receives distributions exceeding 20 per cent of the fund’s net profits.

Slice Distributions

In the framework of such a mechanism, the general partner is entitled to 20 per cent of each distribution but is also obligated to contribute an amount equivalent to 20 per cent of the “return of capital” portion of the securities being distributed simultaneously. This arrangement aims to align the interests of the GP with those of the fund, ensuring that they have a stake in the investments’ success.

Nonetheless, a challenge with this approach arises when the general partner needs to have the necessary cash to make a capital contribution for an in-kind distribution. This situation may lead to distribution delays, potentially impacting the fund’s internal rate of return (IRR).

To mitigate this issue, fund agreements may include provisions for forced distributions or net distributions, where the general partner can fulfil its contribution by relinquishing a portion of the securities it would have otherwise received.

Fund as a Whole Distribution Waterfall Model

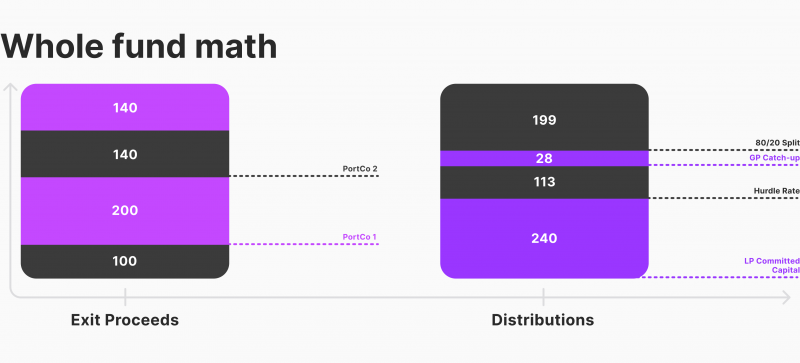

The distribution waterfall in the basic whole fund model ensures that investors are prioritised in receiving their capital contributions back along with a specified preferred return before the manager is eligible for any carried interest.

In the scenario depicted in Figure 1, a single investor invested $5 million in Year 1 and continued to invest over the following years, resulting in a total contribution of $100 million by the end of Year 4. When the initial investment was sold for $12 million in Year 4, all the proceeds were distributed to the investor.

This whole fund model approach delays the distribution of profits to the manager until the investor has received their total capital contribution of $100 million plus an eight per cent preferred return. This model benefits investors by deferring the carried interest to managers, as they receive more of the fund’s profits earlier.

This structure is beneficial from a time value of money perspective, as it prioritises the return of capital to investors before allowing managers to share in the profits generated by the fund.

Hybrid Distribution Model

The hybrid model combines both approaches, where returns are distributed based on specific triggers or thresholds. To illustrate, the general partner (GP) may distribute returns on a deal-by-deal basis until they reach a certain multiple of the fund size; at this point, they switch to distributing returns for the entire fund.

Ultimately, these three models work together to align the incentives of the general and limited partners and offer valuable insights for enhancing the performance of VC funds.

Conclusion

VC fund distribution is a complex and comprehensive process of distributing capital to investors in a startup expecting to receive a return on its success. Due to the wide variety of fund distribution mechanisms, investors are able to choose the optimal participation scenario to maximise the return on their investment while using different liquidity techniques.

FAQs

What is VC fund distribution?

Fund distributions refer to the movement of cash or securities from a venture capital fund to its investors. These distributions are made to investors once the fund has divested its stake in one of the companies within its profile, commonly referred to as a liquidity event.

Who are general partners?

In a partnership structure, a general partner refers to an investor who, along with one or more individuals, collectively owns a business. This individual actively participates in the management and decision-making processes daily, ensuring the smooth operation of the business.

Who are limited partners?

The role of a limited partner in a partnership involves investing money in return for shares. However, their voting power is limited when it comes to making decisions regarding the company’s affairs, and they do not have any direct involvement in the business’s day-to-day operations.

What are the mechanisms of VC fund distribution?

Capital can be distributed to investors in two ways: transfer of cash or distribution of securities in the form of stocks, bonds, etc.